Do psychedelics really always ‘give us what we need’?

In this post, Jules Evans, writer and Director of the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project discusses his latest research on how we experience and make sense of difficult trips, how we process and heal from them, and how we might change the narrative around them.

When I was 18, I took LSD at a rave, and had a bad trip. I felt irrationally afraid and self-conscious for hours, and went to bed feeling I had permanently damaged my brain. Over the next few weeks, I felt paranoid, panicky and socially anxious. These symptoms faded but came back a few months later, and lasted for years. I was eventually diagnosed with social anxiety and PTSD. It took me five years to stop having panic attacks, a decade to regain my social confidence, and longer for me to be capable of having a long-term relationship.

Was that trip ‘bad’? Yes, it robbed me of confidence, scrambled my nervous system, changed my personality and made my life a lot harder. Do I wish it had never happened? That’s a trickier question.

I suspect my life would have been much easier if I had never taken psychedelics. But that adverse experience also had positive impacts. I became interested in mental health, philosophy, spirituality. I experienced ‘post-traumatic growth’, eventually.

And this is the tricky thing about defining ‘bad trips’ – how I labelled that past experience affected my life in the present. When I believed ‘I have permanently damaged my brain’, that became a self-fulfilling prophecy. When I decided it was my catastrophizing beliefs in the present that caused my suffering and I found a more constructive frame for the past, I started to heal.

Today I lead one of the first research projects on extended post-trip difficulties, what they’re like and what helps people who have them. I hope our work can help people in similar situations to the one I found myself at 18.

We’re at an exciting moment when several psychedelic drugs are set to become legalized, whether for recreational, spiritual or therapeutic use, and millions of people could try them. Almost one in five British people are currently on anti-depressants, so the potential market for psychedelic therapy is huge. But how risky are psychedelics? What should people know before taking them? These basic questions are still being debated.

Where do psychedelics really fit on the risk scale of drugs?

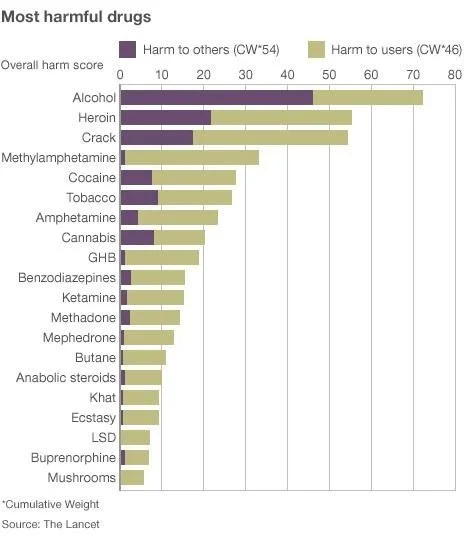

In debates over the risk of drugs, the table here is often produced.

In it, alcohol is by far the most harmful drug, while magic mushrooms apparently have barely any risks at all.

That table was published by Professor David Nutt in 2010, a year after he was fired as the British government’s ‘drugs tsar’ for saying LSD and ecstasy were less risky than alcohol. Nutt is one of the most powerful psychiatrists in the UK, and the graph has been hugely influential – I’ve seen it tweeted twice in the last two days, it’s often used as evidence in the decriminalization hearings now taking place in cities and states around the US, and it’s the graph that persuaded Christian Angermayer to try magic mushrooms and then become the biggest investor in psychedelics. Psychedelics are, according to Nutt, ‘among the safest drugs we know of’.

Nutt’s organization, Drug Science (‘the truth about drugs…free from political or commercial influence’ is its tag-line) recently played a key role in persuading Australia to legalize psychedelic therapy. Nutt was flown over by Mind Medicine Australia to give a series of talks, in which he told audiences that there has never been a psychotic reaction to psychedelics among the thousands of people who have been through psychedelic trials. He also told Australian media that no one has ever come out of a psychedelic trial for depression feeling more depressed (listen to this interview, 7 mins 30 seconds in: ‘no one’s ever come out more depressed). And he has written that warnings of the risks of psychedelics are ‘anecdote and misinformation’, and are a sad legacy of Nixon’s war on drugs.

Nutt’s authority and positive views on psychedelic risk were sufficient to sway the mind of a shadowy figure known as ‘the delegate’, who apparently wields huge power over the TGA, Australia’s equivalent of the FDA. After Nutt’s presentation, ‘the delegate’ changed the TGA’s decision of the previous year, and gave approval for psilocybin and MDMA to be used as psychiatric treatments for treatment-resistant depression and PTSD, much to the surprise of everyone in Australian healthcare.

Some drug experts have since questioned Nutt’s assessment of psychedelic risk. Professor Anna Lembke is Chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic at Stanford University and the author of Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop. She says:

I’ve seen his study cited and presented numerous times as evidence of the relative safety of “LSD” and “Mushrooms” and by inference other psychedelics/hallucinogens, when in fact it does not represent real evidence. First of all, these data are not based on objective findings such as emergency room visits, hospitalization, coroner’s report, or any other standard epidemiologic approach for assessing population harms. From what I can gather from reading the article, these quantitative comparisons are based on a group of individuals sitting around a table reporting their own thoughts about the safety of different substances, based on, well, their own thoughts. The graph also fails to account for is the prevalence of drug use in the population. When drugs are readily available and commonly used in a population, like alcohol, they cause more harm than drugs that are hard to access and less commonly used. The rankings in this graph do not account for prevalence of use.

In other words, Lembke says the risk scores of the drugs in Nutt’s graph were simply decided by Nutt and other members of Drug Science back in 2010, before there had been any systematic studies of psychedelic risks. It’s also markedly different from a list Nutt and colleagues produced three years earlier, in which heroin was rated the most harmful drug, alcohol was fifth and LSD was mid-table. How did alcohol become so much riskier in three years?

Alcohol advocates, meanwhile, say it’s not true that Drug Science presents ‘the truth about drugs…free from commercial influence’ and point out that Nutt has been developing a commercial alternative to alcohol for 15 years, ever since he published the 2010 table, so he has a financial incentive to emphasize the harm of alcohol.

He’s also on the supervisory board of several psychedelic companies, such as Compass, Awakn, Alvarius, Psyched Wellness and Algernon Pharmaceuticals, and his Australia trip was funded by Mind Medicine, the Australian company set to profit from the TGA’s decision to legalize psychedelic therapy. So, according to critics, it is misleading for Drug Science to present itself as ‘free from commercial influence’. On the contrary, the scientists involved stand to make a fortune from our changing drugs landscape. I don’t have any problem with scientists making money from their research - but let’s be honest about our potential conflicts of interest when we’re talking about risks.

It's also not true to say no one came out of any psychedelics-for-depression trials feeling more depressed. In Compass’ big 2022 trial of psilocybin for depression, more serious adverse events – specifically, suicidality – occurred among the psilocybin groups than the control group. In Imperial’s own trials, some participants did initially feel more depressed, before improving. In other trials, we don’t know how individual patients fared as we’re only presented with the average result for the group.

Nor is it the case than no one has ever had a psychotic reaction in a clinical trial, and therefore psychedelics are totally safe in clinical settings. Of the 769 people who have gone through psychedelic RCTs in the last 15 years, I personally know one person who was put on anti-psychotics after taking part in a trial, and another who reported feeling psychotic after taking part in MAPS’ trial for MDMA. Neither of these incidents appeared in the trials write-ups – we heard about them when the participants spoke or wrote about their experience independently.

As for concerns about psychedelic risks being ‘misinformation and anecdote’, this is precisely what Nutt said when SSRI patients warned about adverse effects like withdrawal symptoms a decade ago. In 2014, when patients and doctors formed a group to campaign for better information on the risks of SSRIs (particularly the risk of dependency and withdrawal), Nutt published a letter in the Lancet saying SSRIs were ‘some of the safest drugs ever made’, and adding:

To attribute extremely unusual or severe experiences to drugs that appear largely innocuous in double-blind clinical trials is to prefer anecdote to evidence. The incentive of litigation might also distort the presentation of some of the claims.

It took patients a decade to get the NHS and the Royal College of Psychiatrists to admit that SSRIs can cause withdrawal issues in around half of patients, and for half of them, those issues can be severe. Hopefully it won’t take so long for the psychedelic industry to be honest about the risks of psychedelics.

The ‘bad trips’ rebrand

Nutt’s position on psychedelic risk could be described as secular libertarian. On the other hand, there is the more spiritual perspective found in some of the key researchers at Johns Hopkins psychedelic lab – Roland Griffiths, Bob Jesse, Bill Richards – and also in Rick Doblin of MAPS. This worldview (‘secular spirituality’) sees psychedelics as a catalyst for humanity’s spiritual evolution. In this view, ‘bad trips’ are often better thought of as ‘challenging experiences’.

Johns Hopkins’ psychedelic lab led the rebranding of bad trips as ‘challenging experiences’. In 2016, it launched the Challenging Experiences Survey, alongside a survey of almost 2000 people reporting bad trips, in which 84% of respondents said they felt they had ultimately benefitted from the experience. Another recent paper from Johns Hopkins, based on a language analysis of trip reports, also suggested that trips described as challenging were also often described as healing.

MAPS, meanwhile, suggests on its website that: ‘A true psychedelic experience, even a so-called bad trip, is sacred. In earth-oriented, shamanic cultures, even a psychotic breakdown, induced by a psychedelic, is part of the initiation.’

Many people in psychedelic culture share this opinion. It’s quite common for psychonauts to have a shamanic view of ‘sacred plant medicine’, in which psychedelic plants are spirit allies and there is no such thing as a ‘bad trip’, just averse reactions to the wisdom that the medicine is trying to teach you.

Does the medicine always give you what you need?

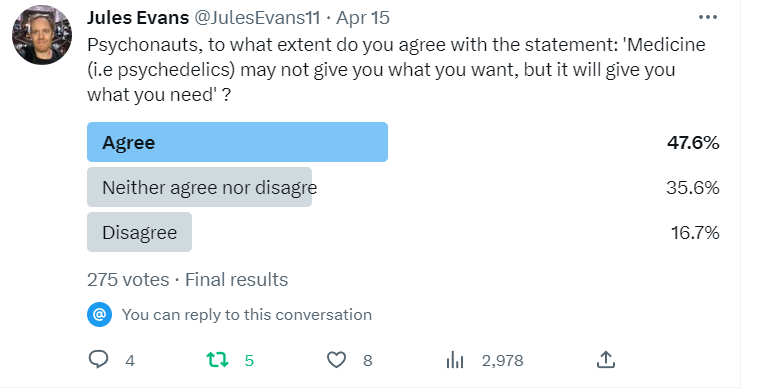

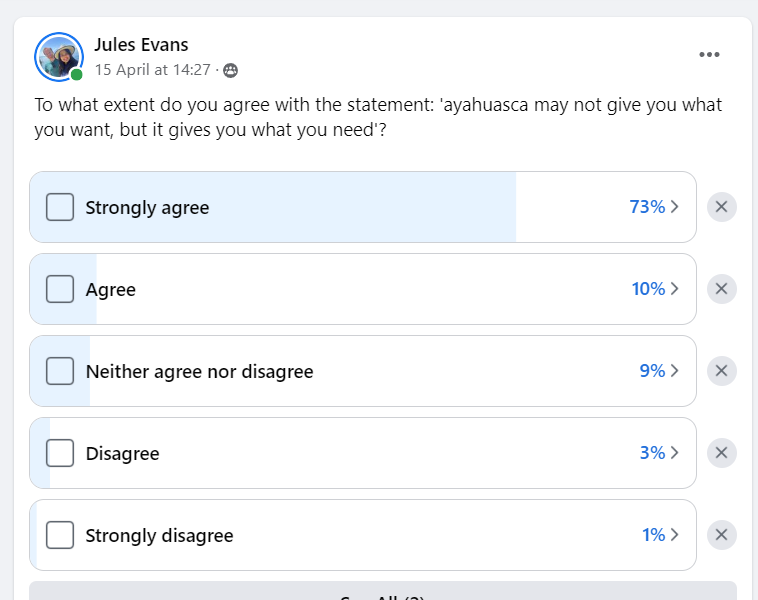

I wondered how common such attitudes are among psychonauts, so I asked psychonauts on Twitter and other social media whether they agree with the statement ‘the medicine may not give you what you want, but it always gives you what you need’.

Here’s what I found out. On Twitter, 276 people replied to my question, and many more agreed with the statement than disagreed:

On the leading Facebook ayahuasca page, there was strong agreement among ayahuasca-users that ayahuasca always gives you what you need:

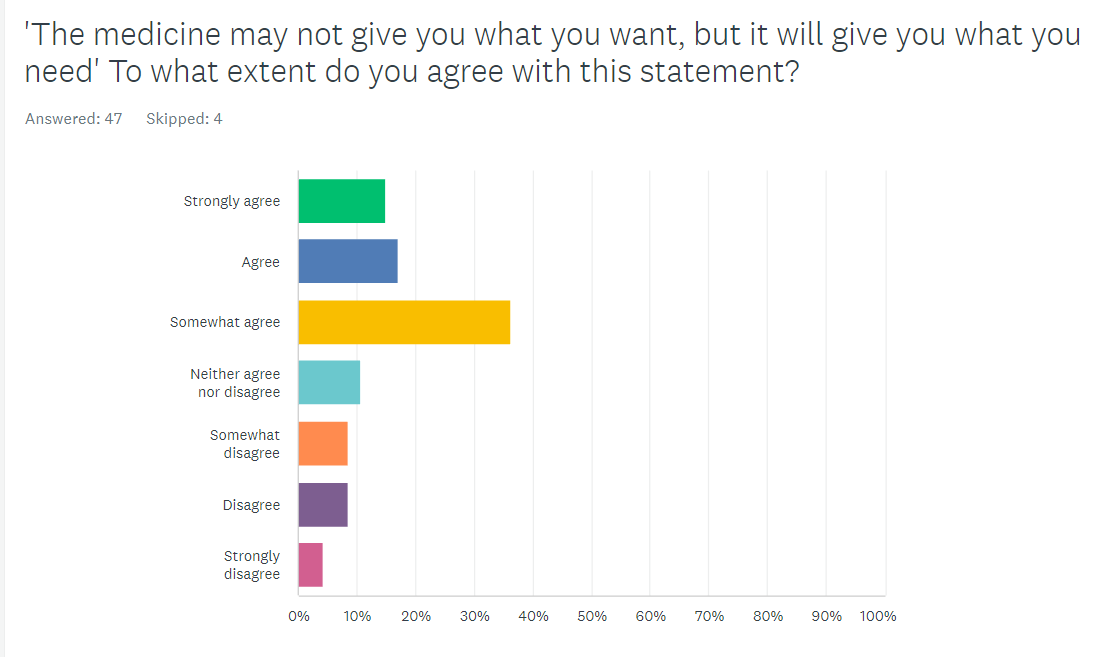

Agreement with the statement also seems to be stronger among psychedelic healers and facilitators than among psychedelic users. I ran two surveys – one for psychonauts and one for psychedelic healers / facilitators / therapists, asking to what extent they agreed that ‘the medicine may not give you what you want, but it will give you what you need’.

Among general psychonauts, 70% agreed – but most only somewhat agreed.

Among psychedelic facilitators and healers (admittedly a very small sample of 8), roughly the same percentage agreed with the statement – but here 35% strongly agreed. In other words, faith in the healing wisdom of psychedelics seems to be strongest among those who sell it and facilitate it.

I am not mocking the idea that ‘a challenging trip is not necessarily bad’, nor the idea that ‘the medicine gives you what you need’. It is certainly the case that sometimes powerfully-healing trips are particularly gnarly, as people confront their darkest and most traumatic experiences, feelings or beliefs.

But the beliefs that bad trips are always ultimately rewarding and that the medicine is never wrong are items of faith, what William James called over-beliefs, like ‘everything happens for a reason’ or ‘God is always looking out for you’. They are theological beliefs rather than value-neutral science.

Over-beliefs can be very consoling for a person and help them make sense of suffering. But it’s different if you are handed such dogma by a healer or therapist when you are having a frightening reaction to a drug. It’s like being told to ‘trust your inner healing wisdom’ when you feel like you’re falling apart. It can lead to victim blaming, as in the meme here, in which adverse effects are your fault for not heeding the medicine’s wisdom.

Sometimes people feel they have been permanently harmed by psychedelics, or their loved ones do. One third of our survey said post-trip difficulties still affected them and 16% of people in Johns Hopkins’ survey felt they didn’t benefit from their ‘challenging experience’. A very few develop long-lasting psychotic conditions after tripping. And some die, through suicide or accidents while they’re high. Some bad trips are just bad – that’s actually a position most people agreed with in our survey of psychonauts’ attitudes. And even prophets of psychedelic spirituality agree with that.

Roland Griffiths is in many ways an icon or saint of the new psychedelic spirituality. But what keeps him awake at night is concerns about harm from the movement he’s done so much to launch. He recently told Don Lattin: ‘People are going to become psychotic. We are in a bubble and that bubble is going to break.’

Roland Griffiths with Don Lattin

The challenges of measuring and defining ‘adverse experiences’

As van Elk et al point out in a new paper on the limits of psychedelic research, there is no settled definition of an ‘adverse psychedelic experience’. Trials classify as adverse events things like vomiting on ayahuasca or ‘seeing things that are not there’ – effects which are very much to be expected from particular psychedelics. Other adverse effects might be crying, resurfaced trauma, anxiety and so on, which again might be considered predictable parts of the healing process. But it’s obviously different if such phenomena occur during a trip, or if they’re still hampering a person’s ability to function several weeks later.

One can talk about short-term, medium-term and longer-term adverse effects. These all occur with psychedelics. In a paper I co-wrote with Anna Lutkajtis, we found that 30% of participants at a psilocybin retreat reported ‘integration challenges’ after the retreat lasting up to two weeks, including emotional volatility, feeling disconnected from home, and post-ecstatic blues. And in our survey of 608 people who have experienced extended difficulties after trips, results from which will be published soon, one third of respondents said they’d experienced difficulties lasting longer than a year, and one sixth reported difficulties lasting longer than three years.

Whether a phenomenon is experienced as ‘adverse’ depends on the person’s expectations, personality and cultural context. One of the most common extended post-trip difficulties reported in our survey was ‘existential confusion’. People’s previous model of reality is blown apart, and that can be experienced as extremely ‘adverse’ – unexpected, unwanted, and harmful to their day-to-day functioning. That existential confusion could be the start of a journey into a richer reality. Or not. At the least, people could be briefed that such existential confusion can arise after trips, that previous models of reality can dissolve or be destabilized, and that this can be bewildering to go through.

To further complicate matters, a person’s assessment of a psychedelic experience and its aftermath may differ to their loved ones or medical authorities. They may think it’s extremely positive and life-enchancing, while their loved ones may think they’ve gone mad, joined a cult, or disappeared down a rabbit hole, all of which would qualify as ‘adverse’.

Perhaps this rough definition will do – an adverse psychedelic experience is one which negatively impacts a person’s functioning in the short, medium or long-term. The psychedelic experience may ultimately be experienced as rewarding and life-enhancing, or not, but can still be experienced as adverse (i.e making life harder) along the way.

There are many challenges in assessing adverse psychedelic experiences. First, as Breeksema et al (2022) noted, AEs have probably been under-reported in psychedelic trials. The problem of under-reporting of AEs in psychedelic trials goes all the way back to the 1960s. Walter Pahnke’s PhD thesis on the Good Friday Experiment, for example, was felt by participants to be ‘all on the positive upside’, in the words of one participant. Thirty years later, Rick Doblin, founder of MAPS, did a long-term follow-up of the study which showed how Pahnke had minimized adverse events in his write-up. But 30 years after that, MAPS faced exactly the same charge from some participants in its own trial of MDMA for PTSD – two participants interviewed by Psymposia felt their adverse experiences were not properly reported in the results.

Every researcher is prone to confirmation bias, but psychedelic researchers are perhaps particularly so, because they are so spiritually, emotionally and publicly invested in the project of psychedelics. Psychedelic researchers get to define what is and isn’t a drug-related adverse event in their trials. For example, in recent trials of Johnson & Johnson’s ketamine spray Spravato, people killed themselves during the trial, but this was ruled by the researchers as not connected to the treatment. Likewise, in Compass’ trial of psilocybin, there were some incidents of increased suicidality, but in an interview with the Guardian David Nutt (who is on the advisory board of Compass) suggested that, in the words of the Guardian journalist, ‘these cases were probably random events and unrelated to the dose of psilocybin, which would have been fully cleared from the patient’s bodies’.

Katharine MacLean, a veteran psychedelic researcher who was formerly head researcher at Johns Hopkins psychedelic lab, has written:

Suicides in clinical trials are being covered up or hidden deep in supplemental sections of papers. I have heard of suicides in psilocybin studies that doesn’t get reported at all, or do not get reported in the main text….I was working at Hopkins as a head researcher and guide when there was a suicide in a depressed man approximately 10 days after he got a ‘disappointingly’ low dose of psilocybin…Why wasn’t this tragic event reported in the main text of the paper. The Hopkins IRB and FDA determined the death was not study related. I beg to differ…He failed to get the promised miracle outcome…and then he killed himself. This seems study-related to me.

In addition, psychedelic research has a positivity bias through its funding model. It’s not just that many leading studies are sponsored and run by companies which stand to profit from psychedelic therapy (like Compass and MAPS). Many other psychedelic trials are sponsored by private philanthropists who are emotionally, financially and spiritually invested in the belief that psychedelics will save humanity. As a result, very few studies on the risks of psychedelics have been funded – although some psychedelic philanthropists have made harm reduction research and services a priority.

Psychedelic culture also has a strong positivity bias. If people have positive psychedelic experiences, they are extremely motivated to talk about them, to discuss them in psychedelic online groups, and to advocate for them publicly. If someone has a negative or extremely negative experience, they are much less likely to want to talk about it publicly, because they may feel shame, guilt, vulnerability or fragility. If they have developed chronic psychosis they may not be capable of filling in surveys or telling their story publicly.

So if you’re assessing the risks of psychedelics by doing surveys of people in psychedelic online groups or listening to testimonials, you are likely to get an unduly rosy picture. One example of this positivity bias in Pahnke’s study. When Rick Doblin did a 30-year follow-up, eight of the nine original participants agreed to be interviewed. The only one who refused was the person who had a very bad trip. We discussed in this piece why we think testimonials play an outsized and distorting role in promoting psychedelic science.

What can we do about this positivity bias?

One solution suggested by two recent papers on improving psychedelic research (McNamee et al, 2023 and van Elk et al, 2023) is to have an independent researcher assessing adverse events on psychedelic trials, rather than the lead investigators. McNamee also suggested researchers should watch out for emergent symptoms. For example, one trial participant told me: ‘Many participants say their depression went down but anxiety levels sky-rocketed. It sometimes feels like we exchanged one problem for another.’ It would also be useful to interview participants at six and 12-months to get a more rounded picture of what got easier and what got harder, and how outcomes may have differed from what they expected.

We should also learn about and better communicate the full range of possible responses to psychedelics, to reduce the unexpectedness of effects and the fear and bewilderment that can ensue. For example:

In one study, 4-4.5% of people who had taken psychedelics reported persistent visual distortions which they found disturbing. (Kurtom et al, 2019)

In the Global Ayahuasca Survey of 11,000 people, 12% said they sought psychological assistance after a difficult trip. (Bouso et al, 2022).

8.9% of psychonauts reported functional impairment lasting longer than a day after a difficult trip, and 6% considered harming themselves or others. (Simonson et al, 2023)

7% of patients in Compass’ trial of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression experienced treatment-emergency serious adverse events. (Compass SEC filing). Likewise, 7% of participants in MAPS’ phase 3 trial of MDMA for PTSD reported increased feelings of suicidality. (McNamee et al, 2023)

39% of people who had a challenging experience said it was one of the five most difficult experiences of their life. Of those whose experience occurred over a year before, 7.6% sought treatment for enduring psychological symptoms. 16% of those surveyed felt they had not ultimately benefitted from the experience. (Carbonaro et al, 2016)

And finally, in our survey of extended post-trip difficulties, early results of which David Luke presented at Breaking Convention this weekend, the most common difficulties people reported were anxiety and fear (panic attacks, fear of going mad, fear of permanent damage, social anxiety etc); existential confusion, derealization and depersonalization, and social disconnection. We also asked what people found most helpful in coping with these difficulties. The most common response was social support – from friends, therapists or people who’ve been through similar experiences. Feeling alone and confused makes these experiences much harder. Information and social support make them easier to navigate.

Psychedelic culture is shifting its attitude to adverse experiences. There can be a tendency to deny and minimize AEs out of fear of giving ammunition to prohibitionists and harming ‘the mission’. This is a mistake, setting the field up for trouble later on when these medicines go mainstream and people report unexpected effects. If we want to support the long-term legalization of psychedelics, we should learn about the risks and what helps people deal with them.

As Rick Doblin put it last month:

The trap that we have to avoid falling into and where the backlash will come from now - if there is - is if we exaggerate the results and minimize the risks. And we have to be very careful that we don't do that.

Jules Evans is Director of the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project and author of books including Philosophy for Life, The Art of Losing Control and Breaking Open: Finding a Way Through Spiritual Emergency (co-edited with Tim Read). This article originally appeared on his substack, Ecstatic Integration.